Photos: Dawn Arrington, Justin Glanville

There’s a resident of Buckeye and Woodland Hills that’s been here longer than anyone else. From the time the neighborhood was mostly open fields and trees - and then through all the changes. The ups and downs, families coming and going, the joys and the heartaches.

Through it all, this resident has stood silent. Barely known. Mysterious. Except for every morning, when:

Bong. Bong. Bong.

"I hear the bells every morning from the church from the abbey in the back where the monks are," says Buckeye resident Dawn Arrington. "And this has always been a place that’s been a little bit shrouded in mystery for me. I wanted to know a little bit more about it."

A Benedictine monastery. Right in the middle of the city.

On this episode of Watershed, The Bells of St. Andrew’s. Or - what’s with those monks at the top of the hill?

Checking out the mac and cheese

St. Andrew Abbey sits at the corner of Martin Luther King Boulevard and Buckeye Road, at the top of a hill with clear views of Downtown - and even Lake Erie, on clear days.

Passing by, you know there’s something there - but you’re not exactly sure what. Dense trees and a low concrete wall line the sidewalks. An asphalt driveway leading back toward a metal gate.

Then you look a little closer, and above the trees you see a steeple. A school bus or two parked in the parking lot. Maybe a few high school boys on their way out to soccer or football practice.

It’s a whole city within a city, not exactly hiding - but not exactly showing itself, either.

Ever since Dawn Arrington moved into this neighborhood, 13 years ago, she’s wondered about the place.

It was a Catholic monastery and high school - she knew that much. But what else? Who lived there? Where did they come from? What did they do all day?

And then one day - in a totally roundabout way - she got an invitation.

"My cousin tagged me in a post on Facebook about all the local fish fries," Dawn says. "I’m scrolling through and said Benedictine what? I had no idea they even did a fish fry. So it’s kinda weird and sad at the same time that something so close doesn’t have that connection anymore with the people that are right here.

"But if the invitation is there and it’s open and it’s macaroni and cheese on a Friday night, I’ma do it," she says with a laugh.

The monks stayed

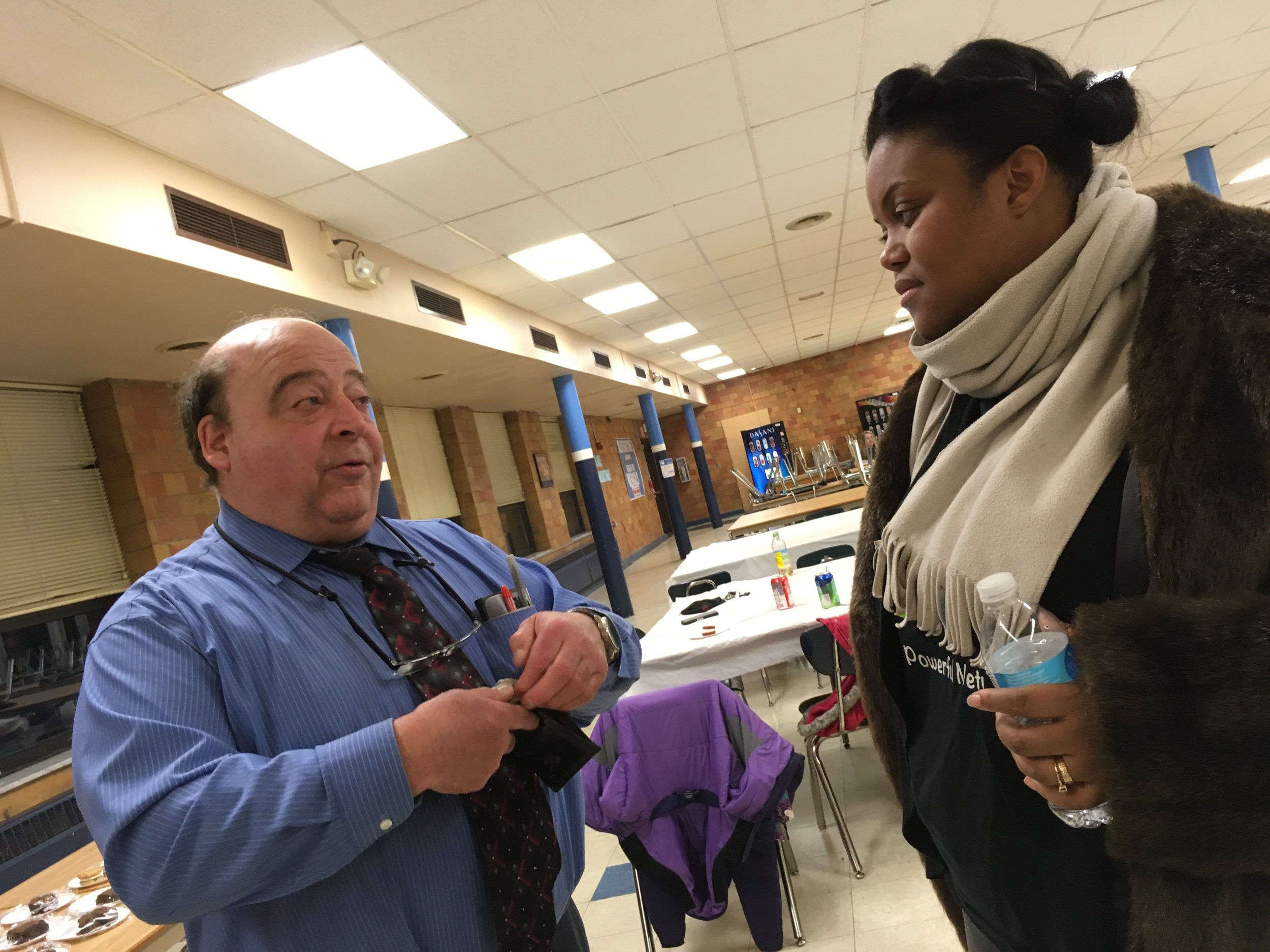

When Dawn and I meet in the Benedictine High School cafeteria in March, the Lenten fish fry season is just getting underway. A few families have gathered - mostly parents of the kids who go to school here.

The first person we meet is Mark Francioli, who's been teaching English at Benedictine High School for 39 years. He also graduated from here, in the early 1970s, and grew up in the neighborhood. He still lives here today, off Larchmere Boulevard near Shaker Square.

"It was an ethnic neighborhood," Francioli tells us. "This particular neighborhood was Hungarian, to the west was a Slovak area, to the north were the Italians."

It was the Slovakians who started this abbey, back in the 1920s. But within 50 years, that population was mostly gone — along with the Hungarians, the Italians, the Irish. They’d left for the suburbs, scared away by some combination of crime, fear-mongering realtors and racial tension.

But the monks stayed.

"They take Benedictine vows," he says. "They take a vow of stability which means they must stay there. don’t have to ever worry about them leaving."

"You know the monks have a rule, anyone who comes to their door, it’s Christ coming to their door, they’re not allowed to refuse anyone," he says.

So — a couple weeks later — that’s exactly what Dawn and I did. Showed up at the door. Well, kind of. We did make an appointment.

Meeting Father Gerard

Father Gerard Gonda is president of Benedictine High School. He also teaches English and theology here, and he’s also a monk who lives at Saint Andrew’s Abbey. He entered the order after a close brush with being drafted in the Vietnam War. (For the full story of his ordainment, check out the podcast.)

He’s in his early 60s. Neatly parted white hair, black coat and pants with the white collar.

We sit down with him in his office. The walls are full of pictures from weddings he’s officiated. There’s a big pro-life campaign sign on the floor, and a piece of paper that says “I’m at a funeral” taped to the back of his door. Ready for the next time he has to go lead someone’s final rites.

Then, Dawn cuts to the chase. What’s up with those bells?

Father Gerard tells us they were installed in 1984 or 1985. At first, the morning bells got a lot of complaints from the neighbors. Then, when they broke a few years later, they got phone calls again -- this time from people complaining the silence made them late for work.

Since he joined the monastery in 1973, Father Gerard says, the neighborhood has undergone a lot of change. White families -- including his own parents -- moved away in droves, and African Americans moved in.

"There was a system where realtors and bankers would scare people that the property values are falling now," he says.

A shooting at a gas station fanned the flames.

"We never had a murder in this neighborhood, and it sent panic waves," he says.

The monastery was under a lot of pressure to leave too. People wanted it to move to the suburbs, or even way out to Medina County, which back then was barely a twinkle in suburban developers’ eyes.

The monks studied for a year, and in 1979 made a decision that their vow of stability wanted them to stay in place.

"Some of our alumni didn’t like it and they stopped giving us money and stuff but other people congratulated us," he says. "And I have to say that for all these years even though the area has had an increase in crime over the years we really have been protected. We've never had a serious crime. I think it’s God’s way of saying thank you for staying there."

Retreat v. community resource

Dawn wants to know how neighbors can meet the monks, and vice versa. She says the first time she ever met a brother was at a doctor's office out in the suburbs.

"I said, 'Oh we’re neighbors, you live at Benedictine,'" she says. "But I had to travel all the way over to University Heights to meet someone."

Father Gerard talks about hosting meetings for neighborhood groups, winter socials for senior citizens, food donation programs. But he admits there’s just a tension that comes with being an urban monastery.

"Of the 30-some Benedictine monasteries in this country, there’s three that are in a city," he says. "Most of them are out in the country. And when you think about monasteries it’s like getting away from the noise and everything."

And that tranquility is a selling point — or, a renting point. You can book a room here. They have five, available for private retreats. And if peace and spirituality aren’t enough to get you to stay, maybe the decor will.

The founder of the Red Roof Inns is an alumnus, and he funded the rooms' furnishings.

"So our guest rooms look like Red Roof Inns in 1985," Gerard says with a laugh.

Bones. Real bones.

But the rest of the monastery looks, you know, like a monastery. Hushed hallways, a lovely cloisters with wind chimes and a wooden porch swing, a library full of books.

There's a Slovak Institute that looks like that trunk of cool old stuff you found in Grandma’s attic as a kid — only exploded into a whole room. Frilly dancing outfits in glass cases, big old hats, maps on the walls, ceramic chickens, shelves and shelves of books…

And then, as we’re leaving, there’s one more surprise.

Bones. Real bones. A glass case full of them, embedded in red velvet. Right in the lobby.

"Sometimes relics are a little chip and put into a nice golden case, and it doesn’t look so gruesome," he says. "But these were gotten in Europe in the 50s and they’re a little more dramatic."

Curiosity and invitations

We say goodbye to Father Gerard, thank him for his time. Dawn says the shroud of mystery has been lifted.

I ask her for some closing thoughts.

"I think the thing that stood out most to me was this almost unsolicited admission that the community that’s within Benedictine and the community they’re located within, we both have work to do to bridge the gap, and learn more about each other," she says.

She says that could start with little things: Going to fish fries, community open houses at the monastery.

She'd like to see the neighborhood become more curious, and to the monastery do more inviting.

"Right now the invitation is not widely known," she says. "So the work on the school’s and monastery’s side is to make the invitation, but then on our side when the invitation is made, don’t question it. Just try it."

And as we step outside, as if on cue -

Bong. Bong. Bong...