There are a lot of ways that Michael Payne is striking. When I meet him after rehearsal for a play he cowrote and stars in, we cover a head-spinning amount of ground in just an hour-long conversation.

He tells me how he used to be a salesman for Bloomingdales department store in his hometown of New York City.

He tells me how he’s worked in Memphis as a car salesman. Flew to Trinidad to try to charm the father of a woman he loved. There’s laughter, there’s anger, there are tears. There are foreign languages.

All this energy, all these eccentricities: They provide a lot of the material for Odysseus Unraveled. That’s the name of the play he’s cowriting and starring in, part of a series of new plays in development at Cleveland Public Theatre called Test Flight.

But Michael is like a lot of artists, in that the stuff that’s fueling his creativity now was painful in the past. Growing up in New York in the 1960s and 1970s, he felt really different from everyone else.

"I cried all the time," he says. "My nickname was crybaby. There was times I cried all month and my mother told me if you keep crying I’m gonna have to put you out of here."

He says he has no idea how he’s so sensitive, because his two brothers were both tough guys. While they were out getting into fights, he was hanging around with an old German woman in a deli across the street from where he lived.

Eventually, while he was working those sales jobs in department stores, he got mugged a couple of times, and he says it sent him into a tailspin. He was afraid all the time. Drifted in and out of work, wasn’t able to hold down jobs anymore. Got into drugs.

Somewhere in that rough period, he moved to Cleveland. A friend took him to a psychologist, who diagnosed him as bipolar. At first, it was hard for him to accept.

"Bipolar?" he remembers thinking. "That’s what white people do. Here's what black people do: If there's a problem, we go to church."

Writing his story

But he started therapy, eventually got sober. He was able to go on disability, which gave him a steady if small income.

And as his life stabilized, he started writing down stories. Memories, in poetry and prose, of his life. About his past jobs and loves and addictions. He filled pages with reminiscences and reflections.

"To my mother, I'm her favorite child, her shining star. But she doesn't know in reality I'm an addict..."

The problem was, he didn’t feel like he had much of a present. He didn’t have a job, not many reasons to leave the house, and he says the less he got out, the less he felt like getting out.

That intensified when he moved to Buckeye a couple years ago. He didn’t know any of his neighbors, and his way of coping was to hole up.

He closed all the windows, drew the shades. The only time he went out was to go grocery shopping or to doctors’ appointments.

Loneliness happens everywhere, of course, for different reasons. In a wealthy suburban neighborhood with lots of space between houses, maybe you don’t have many opportunities to run into people organically and make new friends.

In Buckeye, the things that may keep people inside are a perception that their neighborhood isn’t safe. Mental and physical illnesses that may be caused or made worse by the stress of poverty.

Something in Michael, though, told him he had to make a change.

"I started to reach out to people because I was so lonely," he says. "I knew i needed someone to talk to because now I have nobody."

Meeting people

At first, he did that in a way that felt safe. He got on Facebook and found some old friends.

It helped a lot, having those online conversations. But for the next step, actually meeting real people in the flesh, he got a little help. It happened one day as he was coming home from a doctor’s appointment.

"A gentleman across the street offered me to go to [Neighborhood Network Night] to meet your neighbor. I said, 'What better place to go to meet people because I live here and I don’t know anybody.'"

I asked him what drove him out of the house.

A potluck turns to drama

At the meeting, this one woman stood up and invited everyone who was interested to come to a community garden she helped run about a block from Michael’s house.

Michael thought, 'Great. I like gardening and cooking.' So he screwed up his courage and rode his bike over that weekend.

He came back later for a potluck, and had great time. People loved the Creole chicken and rice he cooked with vegetables from the community garden. He had some good conversations. Then, the night got even better.

He heard piano music from inside the house next door, where the woman who first told him about the garden lived. Michael loves music, so he went to check it out.

The player was a guy he’d never seen before: Daniel McNamara. The owner of the house, and also one of the founders of the community garden. They kept singing and playing together, and Michael told Daniel his life story.

Daniel was as struck by Michael as Michael was by him.

"By the end of the story he’s weeping, this guy I just met," says Daniel. "He clearly had a lot he needed to share."

As fate would have it, Daniel is a playwright and performer. He’s naturally drawn to other storytellers. He invited Michael out to a diner a few weeks later, so they could talk more.

Michael showed up with a sheaf of handwritten papers: the writing he’d been working on during his time alone in his house.

He started reading, and Daniel thought it was beautiful if heavy stuff. A memoir of addiction, despair — but also recovery.

As eggs and burgers sizzled on the grill in the background, an interesting thing happened.

"As he’s telling it," Daniel says, "the waitresses in the diner are all freezing and listening and going, 'What are you working on?' And they’re all compelled and I’m just realizing this man has magnetism."

By the end of the meeting, Michael could tell Daniel was shaken.

"I looked at him and I said 'What’s the matter?'" Michael remembers. "He said, 'That’s amazing you survived that.' I said the only thing I’d like to do is leave my legacy, to help somebody who’s stuck where I left."

A crazy idea

Eventually, Daniel got an idea. By this time, he’d already been approved to develop a new play at the Test Flight series at Cleveland Public Theatre. Pretty much all he knew is that he wanted it to be inspired by the ancient Greek epic The Odyssey. And he realized something.

"I don’t want to do just a solo show for this," he says. "I want to work with people. And --" he snaps his fingers -- "'Michael Payne! Michael Payne could be in this show! That’s a crazy idea but a great idea."

For one thing, there were some clear parallels between Michael’s story and the story of Odysseus. This man who gets swept up in a storm, and encounters a bunch of dangerous obstacles, before finally returning to safety.

But it was Michael’s presence that attracted Daniel more than anything else.

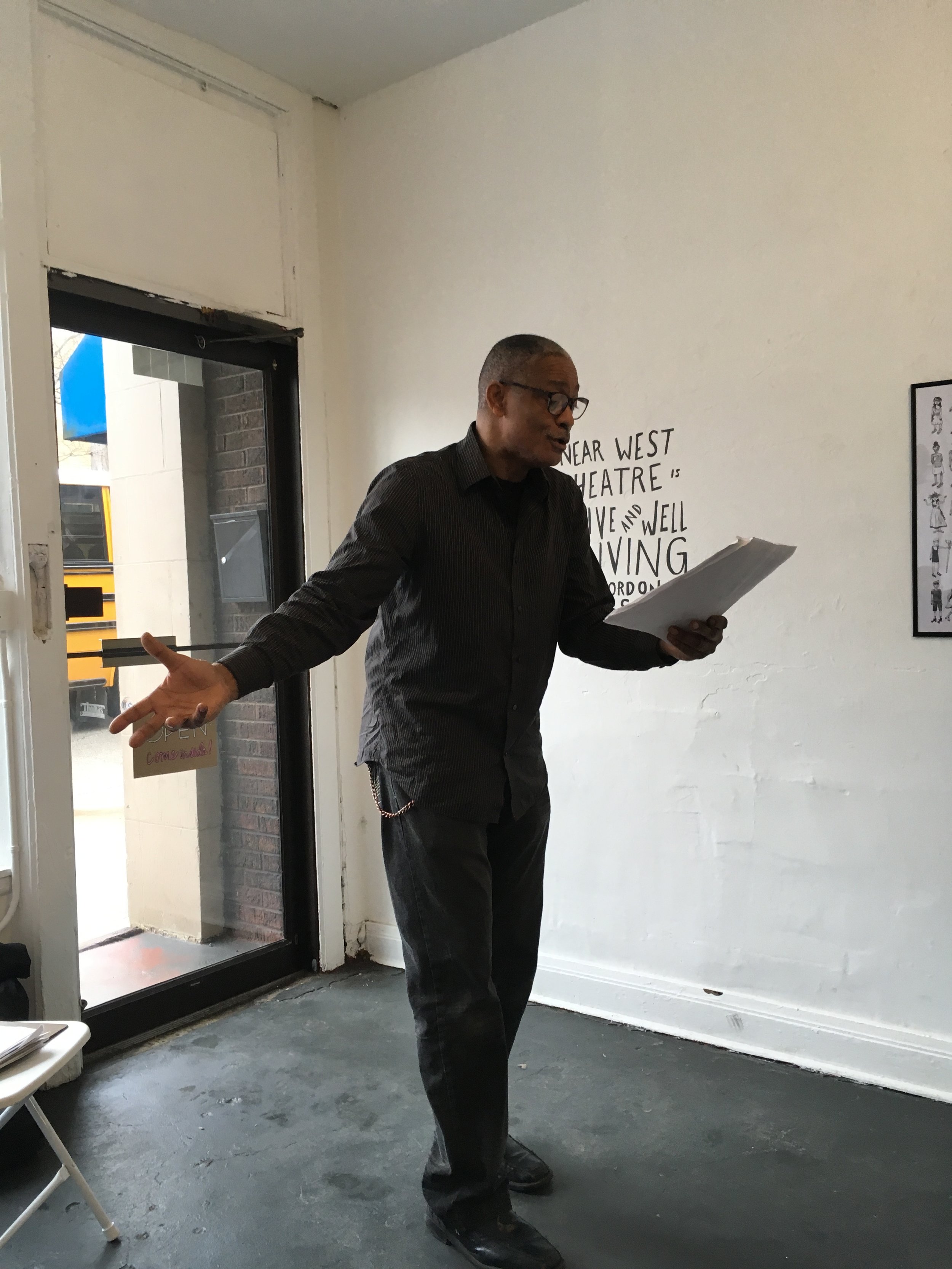

"The degree of storytelling, the degree of detail, and the emotional intensity of really being drawn back into that moment - it’s this amazing talent he has," says Daniel.

Daniel pitched the idea of a collaboration to Michael. Michael was excited, but nervous. He’d never acted before, but also the rehearsals were gonna be on the West Side. Which would mean he’d not only have to leave his house but take a 40-minute train ride across town.

Telling the story now, he still gets stressed out -- but he made it.

That was also when Michael met the other performers and co-creators of the show — actresses Diana Sette and Monica Idom; and musician Jonathan Apriesnig, who’d be improvising music while they performed. It was all a lot to take in, and Michael pulled Daniel aside.

"I said, 'Daniel, listen to me. If i’m not good at this stop it, because I don’t want to be embarrassed.'"

By the end of that first session, though, Daniel told Michael he had nothing to worry about.

"He has this unique view of the world and there’s a lot of kinetic energy," Daniel says. "And that’s extremely interesting to me. Instead of trying to get somebody moving and get their brain going and get them to tell you something, with Michael it’s like --"

He blubbers his lips in an imitation of an explosion.

Proud of me

Flash forward a few weeks, and far from being fearful, Michael can hardly stay away.

"He’s there on time, he’s there every time," says Daniel. "He’s there early sometimes because he’s so excited."

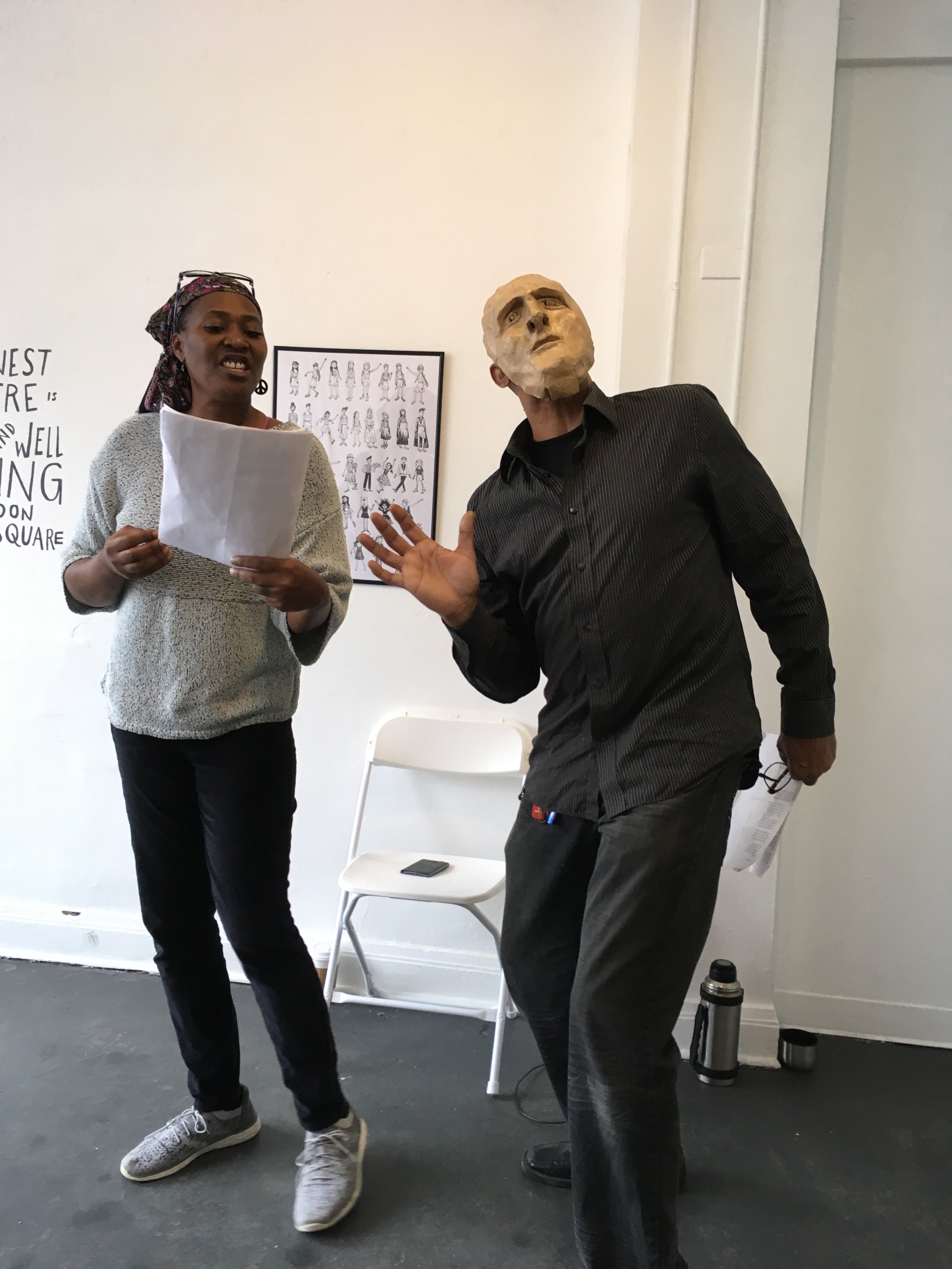

As I watch Michael rehearse, I’m struck by how easily he fills the space. One moment, he’s swooping around, ducking and snaking his body around Monica Idom as Athena. The next, he’s wearing a papier mache mask - of a man’s face, his mouth open in either wonder or fear.

As the play is ending up, it’s a mix of stories taken from Michael’s life and these more impressionistic sections inspired by myth. I ask Michael what he thinks are the similarities between himself and this Greek hero from thousands of years ago.

"Odysseus is a man who’s resourceful, he’s like a chameleon," says Michael. "He’s a multiple personality type character, which fits me well."

He’s also going up against forces that feel far more powerful than he is. But not giving up.

If there’s one potential drawback to all this creative release, it’s going to be dealing with the end of things. What happens after rehearsals are over, after the curtain falls.

Michael and Daniel are planning to work together on turning Michael’s writing into a book that he’ll self-publish. But the ending of any project - especially one that’s so public - can come with a feeling of anticlimax that Daniel knows well, being a performer and writer himself.

In this case, that's complicated by the fact that Daniel's a middle-class white guy, while Michael's an African American man living on disability, with mental illness.

"Yeah there's potential negative impacts of sharing this creative process that I have the privilege of accepting as a part of my life that many people don't view as accessible to them for lots of systemic reasons," he says. "But the closest thing i have faith in is art and creativity. I believe that in sharing that and inviting others and including others, I believe in the importance of it, that we need that."

Michael says he believes that, too.

I ask how he thinks of himself now.

"I’m proud of me right now," he says. "At this point in my life, I have nothing to prove, nothing to gain, so honesty will set me free."

He says, no matter what happens when the show ends, he’s not alone anymore. Not only does he have Daniel and his other collaborators in the play, but he has all his Facebook friends, old and new. He has the neighbor across who invited him to the network night. He has all the people he met in the community garden last year.

Summer’s coming, and he’s ready to sing and cook more Creole food. And who knows what will happen from there.